We speak to Joe Caithness, mastering engineer for many a Laced Records release, about the end-to-end mastering process, living the vinyl lifestyle and the importance of archivism.

By Thomas Quillfeldt

The process of music mastering is a somewhat mystical one, inviting metaphorical description: it’s the ‘icing on the cake’; it’s the ‘magical fairy dust’ sprinkled over a track; it’s one of the ‘dark arts’ of music production.

But what we have here is a real, live mastering engineer — regular Laced Records collaborator Joe Caithness of Subsequent Mastering — to help us understand the ins and outs of mastering, how it fits into vinyl production and whether video game music requires any special consideration.

Hey Joe

Nottingham-based Caithness has been a mastering engineer for 10 years, despite only just entering his 30s. Like so many in audio engineering, he’s explored a multitude of musical avenues from a young age: successfully touring and releasing records with punk/hardcore bands including Plaids, What Price, Wonderland? and Soul Structure; running a label (Special Stage Audio); helping to set up a venue (Nottingham’s JT Soar); as well as DJing (in clubs and on the radio) and producing electronica as Littlefoot. His travels and travails have seen him embedded in numerous genres, from early ‘00s DIY punk, through dubstep and electronica, to grime.

But the growing demand for his mastering skills has seen it become a full time job, which he balances with a penchant for collecting a metric tonne of records and exploring the ins and outs of audio archivism as well as manually building a brand new mastering, restoration and audio transfer studio (in the back garden).

Through all of it, Caithness has maintained a love of video games and game music, sprinkling various VGM samples throughout his creative projects; and, over the last few years, he has helped Laced Records produce a diverse range of game soundtrack releases, including for The Talos Principle, Yooka-Laylee and the Hotline Miami Collector’s Edition Vinyl.

The titles Caithness mastered for Laced Records in 2017:

Mastermind

Caithness can’t resist proffering his own metaphor about mastering: “You might think of it in terms of an art gallery hosting an exhibition. The artist chooses the paintings to be displayed, but the gallery curator chooses where to hang each one, how to light it, the temperature of the room and so on. The paintings themselves are what’s important, but all these variables could change or ideally enhance how the viewer enjoys the work.”

He’s also keen to clarify the wide range of processes that are covered by the term ‘mastering’: “There is a bit of confusion, as some people think mastering is just spicing up or sweetening audio. That’s certainly part of it, but in a lot of cases there’s more to it. “It’s all about who’s going to be handling the audio next, understanding where the audio is going to end up and how it’s going to be listened to — then preparing it based on those things.”

A given job could simply mean receiving digital files over the internet, applying some audio processing using only software (AKA ‘in-the-box’) and sending it back to the client. Or a project could involve physically searching for and weighing up the best audio source with the production team; transferring old reel-to-reel tapes to hi-res digital audio; using analogue outboard equipment to process it; and smoothing out EQ problems with the music that might give the vinyl plant engineer a headache. There’s also a job to do ensuring that the resulting digital file types and all of the information that’s within the delivered file or physical disc or tape (AKA ‘metadata’) is correct.

Caithness points out that his work for Laced Records has covered almost the entire range of different mastering tasks, and he’s relished the challenges thrown up. “It’s what separates a mastering engineer from ‘someone who masters stuff’ — being able to understand the scope of the project, as well as the musical and technical subtleties involved.”

He stresses that mastering engineers are supposed to take a holistic view of the audio, and it often helps that they are coming completely fresh to a project rather than having heard it repeatedly over the course of months as the artist, producer and/or recording engineer would have done.

“Ultimately, mastering is the process that links the production of an audio product (writing, recording and mixing) and the manufacturing and distribution — a mastering engineer conveys the audio between those two worlds.”

According to Caithness, audio engineers (including recording and mixing engineers as well as mastering) sit somewhere on a scale from the musical and artistic mindset at one end, to the technical and engineering mindset on the other. As a mastering engineer (with a background as a music artist and producer), he thinks of himself as sitting somewhere in the middle, preferring not to be associated with one particular genre or audio processing technique — an audio agnostic.

Format forethought

Tweaking audio is indeed a core part of the mastering process, and what the engineer does (or doesn’t do) is governed in part by where the audio will end up. Caithness explains: “There might well be some equalisation [tweaking different frequencies across a track] or compression or limiting [using tools to manipulate the volume and sense of ‘loudness’] involved so that each master file is suitable for its respective playback scenario,” e.g. to be listened to on iPhone headphones via Spotify or on £10,000 speakers on vinyl.

“A phrase that we use a lot in mastering is ‘fit for purpose’. It’s not necessarily that you’re changing the EQ, compression or other processing for each possible destination, but you have to be aware of them as you go.” He gives the example of the soundtrack release to Yooka-Laylee, which was released on 12-inch vinyl, CD, as a digital download and on streaming music services. “It has to be consistent so that if someone invests their time and money to get the deluxe vinyl version, they won’t be let down; similarly if someone puts the odd track from the album onto their ‘Favourite game music’ playlist on Spotify, it has to sound great in both places.”

In practical terms, Caithness will produce different digital files — Waveform Audio Files or WAVs — for each respective format.

For vinyl, the digital file that goes to the cutting engineer at the pressing plant is called a ‘pre-master’, as the ‘master’ in the case of vinyl is a physical disc. Instead of there being as many WAVs as tracks on the album, he creates one long file per disc side (in the case of Yooka-Laylee, this means four files — two discs x two sides). “Those vinyl pre-master files have a bit depth of 24 bits (CD is 16 bits), usually with a sample rate of 44.1k because that’s often the standard at which the audio comes to me. You keep the audio sample rate the same as that which you receive — you don’t change anything unless you need to.”

Mastering The Talos Principle ~Made Of Words~

Caithness worked with Laced Records on the vinyl release of Damjan Mravunac’s soundtrack for first-person puzzle game, The Talos Principle (Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube). The project was relatively straightforward in terms of mastering, as the soundtrack had enjoyed a well-produced 2014 digital release around the same time as the game; also, the composer was the same across every track and there was no trouble sourcing the original audio sessions in order to obtain the highest possible quality (unmastered) mixes of the tracks.

“You could tell that it was quite a high concept production for everybody who was concerned, and [developer] Croteam are a tight-knit bunch. They’ve got their own dynamic and energy and it works really well, so I had to be very respectful of everything that they’d done with the audio up to that point, and mindful of everything they were trying to achieve with the vinyl release.”

Indeed, Mravunac’s tracks were so pristine that all Caithness needed to do was some subtle equalisation: “There was no compression, no limiting and no fancy stuff required.” Although much of the instrumentation is virtual, as Mravunac talked about in a recent Laced With Wax interview, Caithness found that mastering the project felt like handling an orchestral recording: “It’s about not treading on it and being as transparent as possible. It was all done digitally at a really high resolution, keeping it pristine and making sure that it sounded suitably organic — as the composer had already put all the hard work in to make it sound wonderfully ethereal and otherworldly.”

Special considerations for vinyl

Caithness points out: “When it comes to creating the vinyl pre-master, as opposed to the CD or digital master, there is one thing in particular that you don’t do — and I’m guessing this is why some modern vinyl products don’t sound as good as people would like them to — you don’t apply any of the processing for digital loudness.”

What he alludes to is what is known in the audio industry as ‘The Loudness Wars’ (explained here by Curiosity). Put simply, over the last few decades, almost everyone involved with popular music production has been using techniques (enabled by digital audio technology) to make their tracks sound louder and louder in competition with one another. An early example of this is The Red Hot Chili Pepper’s 1999 album Californication, where the dynamic range of the tracks was severally squashed using compression and limiting to make it all sound as loud as possible. In the particular case of the original CD release of Californication, it could be argued that this was done for effect, but it led to complaints about digital clipping and distortion — and yet went on to serve as inspiration to other artists and producers that louder tracks were more likely to grab listeners’ attention.

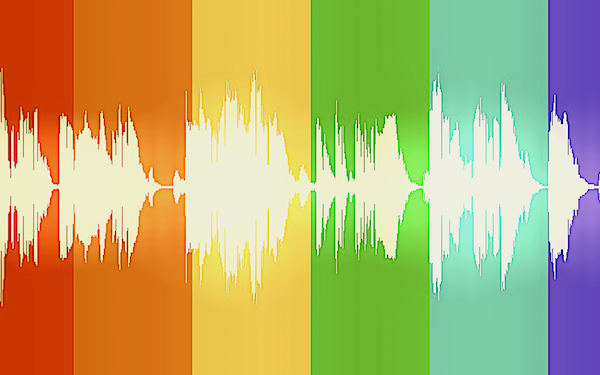

“A CD or digital master would usually be hitting the very top of the digital scale (AKA 0dB or zero decibels — the average threshold of hearing for the healthy adult ear), probably with some peak limiting, and it would look like a larger, squarer waveform.”

A modern pop track (Hello by Adele), mastered for digital:

“Whereas with the vinyl pre-master, the peaks are preserved, unchanged. So all of the transient information — for instance, fast sounds — makes it onto the vinyl directly from the unmastered original file.”

In layman’s terms, this means that the loud bits of a track will vary more naturally in how loud they get in terms of actual volume, and for how long they stay loud; similarly, the quiet bits will seem quieter by comparison. This is known as the dynamic range. Caithness adds: “In a way, the vinyl pre-master file is the ‘cleanest’ version of the audio.”

(Top) the CD and digital master waveform for Grant Kirkhope’s World 3 Theme from the Yooka-Laylee OST; (bottom) the vinyl pre-master waveform:

It’s a little bit like the contrast between the blacks and whites on a TV. Currently, HDR or ‘High Dynamic Range’ (blacker blacks, brighter whites) is being touted as a fancy new feature on new TVs. A well-produced vinyl tends to preserve a greater audio dynamic range.

“This kind of processing to boost loudness is not invisible, so when you’ve got a loud CD or a loud digital audio file, an extra layer has been applied (at least, that’s still the trend) that is often not a positive change — whereas you simply don’t apply that extra layer to a vinyl pre-master.”

The other side of mastering for vinyl is about knowing about where the audio is coming from and where it’s going to. As an audio expert and avid crate-digger, Caithness has no compunction pointing out the audio limitations of the beloved vinyl format: “There are certain physical limitations, based on the fact that it’s a single groove cut into a disc.

“This mostly concerns the levels of certain frequencies, such as really, fast high frequencies (e.g. sibilance on vocals, hi-hats or certain electronically created sounds); also at the other end, there are problems with reproducing extreme low-end, and especially extreme bass which has any sort of stereo effect on it. If you breach one of these, the people at the vinyl pressing plant will just say ‘I can’t deal with this’; or they’ll have to make compromises, over which you have no control, just to get something onto the disc.”

Mastering Hotline Miami: Collector’s Edition Vinyl

For Caithness, the Hotline Miami: Collector's Edition Vinyl was almost the opposite of the The Talos Principle project, and a good example of where his mastering experience was put to the test. After all, Hotline Miami’s soundtrack is a sizeable compilation of tracks by nine different artists, which led to a number of issues that needed smoothing.

“The developers [Dennaton Games] sourced the music for the original game by scouring BandCamp and SoundCloud for electronica tracks by independent artists to find things that matched the mood of the levels. That was 2011/12... When it came time to put together the tracklist for the vinyl in 2016 [including four bonus tracks], there was about as wide a range of digital audio sources as you could imagine.”

In some cases, the original Pro Tools/Digital Audio Workstation sessions were unavailable, meaning that Caithness had to work with what he received in terms of digital files. “There was a lot of back and forth about getting hold of the best possible versions. Some of the tracks had already been mastered by the artists themselves [something that’s common amongst electronica producers] and the original unmastered mixes were unavailable; whereas other tracks I received were cleaner. No disrespect to the artists — they were just doing what was natural to them at the time when they were making the tracks, and they probably didn’t think they would end up on vinyl.

“There were already a lot of fans that had put their money down through the Kickstarter campaign, so we had to work hard to make the record a consistent listen and clear up any problems for the pressing plant. Luckily it came out A-OK!”

Caithness’ pride over the project is evident: “You need to build up the experience to know when to go in with a sledgehammer and when to tickle it — and then possess the tools and the skills to apply that. But if you don’t have that in the first instance, you’re not going get a good output, irrespective of your credits or your gear.

“That’s why I get a kick out of doing the soundtrack stuff. Musically and technically, they couldn’t be any more different: Hotline Miami compared to The Talos Principle; Yooka-Laylee to Ruiner. They’re all completely different concepts as far as sound production goes. But since they’re all going onto disc and appearing in the Laced shop, there’s got to be a certain level of quality and consistency there.”

Check your sources

Whether it’s a project that’s been converted to hi-resolution audio from the original reel-to-reel tapes, or a spruced up rip of a bootleg cassette, where audio comes from greatly affects Caithness’ approach to mastering and also serves as a source of scholarly fascination for him.

As an ardent collector, he often ends up with multiple pressings and reissues of the same album; and, as a connoisseur of punk from across the last 40 years, he’s come across all manner of releases in terms of audio quality: “There’s been a recent trend — especially with punk records made in the ’90s when vinyl was out of fashion — to press records from the CD, as there were no vinyl pre-master and no original recording tapes available. That’s not to say that this is inherently wrong, and the mastering engineers are doing the best job that they can do with what they have — it’s a viable product because people are paying good money for this stuff. But it does make me appreciate when people cut from the original tapes.”

Caithness himself has found a niche creating vinyl pre-masters from archive material, using vintage equipment to transfer tapes for instance. “It’s really important how you handle the materials from the very earliest stage.”

But it’s not all about golden oldies on analogue formats. There are several generations of digital music that also have to be dealt with in a thoughtful way. A self-proclaimed nerd around the topic of digital archivism, he points to those who go to lengths to build old PCs to access otherwise irretrievable software and files. Some of his clients have made sure to record midi tracks off of specific older PC sound cards; or they’ve gone back to the original digital multitrack sessions running on older software or digital recording hardware.

“Take music recorded during the early days of hard disk recording: there isn’t a physical tape, and there are moving parts and components in old disks that are basically dead, or need some work. We’ve seen several generations of people transferring analogue ¼-inch tapes to hi-res digital; and there’s going to be a generation of people transferring digital formats like MiniDiscs, DAT tapes. They’re hardly hi-fi formats, but if that’s where the audio is, as a mastering engineer you need to know how to get it off properly and to move it onto the next stage.”

Physical formats including a MiniDisc, a Data8/D8/exabyte tape and a DAT tape:

“When people do reissues of, say, The Beatles, they look for the best tapes and the most appropriate playback machines. It makes perfect sense to me when remastering video game music, especially from the 90s, that you would adopt the same philosophy and not bypass those extra stages of retrieval and recreation. Because it’s important to stay faithful to how the music was written to be heard. The intention of the composer might have been for a given piece to be heard by way of a Sound Blaster 16 on a Gateway PC, or on a SNES sound chip — to me, that’s as legitimate as playing an old blues recording through a mono Studer valve tape machine.”

“It’s all about what’s available. The labels that do their research and go the extra mile will always get a better product; and I think that people who buy those products do appreciate the extra work that’s gone in.”

The digital black hole

Of course, one of the driving force of archivism is the concern about the loss of swathes of material from various eras. “Hard drives are now dying, older machines with moving parts are dying. I’ve been helping various clients transfer projects and audio off of old drives and machines. So when we’re ready to re-master things, we’ve got what we need.”

In particular, there was a period during the ’90s where CD versions of tracks exist (of varying quality) but from a pre-internet era (so no online back-ups), and the original multitrack sessions languish on old digital systems. Musicians of a certain generation — for instance late Baby Boomers/early Generation X’ers (Gary Numan et al) — are engaging in complex archival projects to rescue and preserve their material.

One of Caithness’ projects, for folk revival singer Bert Jansch, involved retrieving tracks from exabyte digital storage tapes: “The ones and zeroes have to reach a certain point on the tape, and if it doesn’t go beyond that, there’s an error and it drops out. We had to find a copy of a particular CD (which wasn’t going to last forever) and match it up with as much of the exabyte tape as we could transfer to make the pre-master for vinyl.”

That edgy N64 sound

All of Caithness’ favourite video game soundtracks come from eras where the limitations of console sound chips inspired ingenuity in game composers.

“The music for Marble Madness on the NES blew my mind because it explores keys outside of the standard major and minor ones that other games stuck to. It also introduced me to intense jazz scales, kicking off my love of jazz greats like Thelonious Monk — especially where he plays with landing on the wrong note to essentially wind up the listener.

“Level 4 of Marble Madness is prefaced with the statement “Everything you know is wrong” and suddenly the marble is going upwards instead of downward — correspondingly, the music goes really atonal and as a kid I found it genuinely frightening.”

Mega Man 2 is also a firm favourite: “It’s best platform game ever made, and the way the aesthetic of the levels matches the audio is absolutely bang on.” Caithness wove the Metal Man level theme into one of his numerous game-inspired tracks — in this case a grime remix:

But above all, he’s a devotee of music from early Nintendo 64 games, including David Wise, Eveline Fischer and Robin Beanland’s score for Diddy Kong Racing: “The music is perfectly matched both to the overall aesthetic of the game and within each level. When I think of Diddy Kong Racing, I can match sounds, keys and visual colours all in one thought, evidence to me that the composition was next level.”

This passion meant that Caithness was doubly excited to work on the Yooka-Laylee soundtrack, which sported tracks by, among others, the aforementioned Wise and fellow Rare alumni Grant Kirkhope (Banjo-Kazooie, GoldenEye 007).

“A lot of those games sound very similar to music made using the Korg keyboards of that era (e.g. Triton and Trinity); it’s basically the sound of that generation of digital sampling. There’s this graininess to the samples and, when they’re layered upon one another, it creates a particular harshness, an edginess to the overall tracks. In a way it’s similar to ’90s hip-hop created using cheap samplers. People hated that sound then, and it hasn’t exactly aged well, but for my generation it’s interwoven with emotional memories of playing those games; riding around Hyrule on a horse or escaping Tricky the Triceratops.

“I’ve always been impressed by those composers and soundtracks, and been fascinated by how they could create music that withstood listening to over and over again — I must’ve heard those Diddy Kong Racing tracks more times than my favourite punk album.”

The vinyl lifestyle

As long as he’s been into music, Caithness has also been been dedicated to music on physical formats, first putting out his own vinyl at the age of 15 via his fledgling punk label. Like most keen collectors, he’s both open-minded to the new, and dedicated to charting specific historical niches — including mid-’90s EMO and early ’80s anarcho-punk.

“It’s not just about vinyl but about the physical medium in general — books, CDs, cassettes etc. Obviously vinyl is having a popular resurgence for many reasons, but it’s not the sound that’s the thing — getting good playback on vinyl is a right bastard sometimes — the most important thing for me is the series of real world interactions, the whole lifestyle around digging for interesting records and making time to listen to them. I contend that as a hobby, it’s good for your physical and mental health!

“My music room is filled with records sorted by genre; I’ve also got a stack of jazz cassettes to go through, a pile of vinyl to clean and so on — real things to interact with. I almost don’t like the phrase ‘record collector’ because I don’t collect, I use.

“And it’s a hobby that gets you out of the house! I picked up 10 LPs from a flea market the other day… You buy some records then go to the pub and show your mates what you’ve picked up. There’s also something about not knowing what you’re going to buy when you go to a record shop, giving yourself over a little bit to the artwork, the liner notes and the way it’s been arranged. I buy hundreds of secondhand records — I never go to a city or a town without buying a record. I buy different versions of the same record… It’s hard for me to even describe it because it’s been my life since I’ve been aware of my own life! Buying new and old records, picking stuff up, selling stuff and so on.

“I really hope that younger generations are pulled into this world by way of getting a Hotline Miami set for Christmas because they love the game and music, for example. They missed vinyl the first time around, but also didn’t have bands they liked offering them vinyl as an option until more recently. They see the original artwork and are tempted to pick up a cheap little turntable (which can be pretty damaging to records!)… to make the best of the turntable they pick up their favourite albums on vinyl as well… maybe the next year they’ll invest in a Rega or Projekt turntable.

“You overhear younger music fans in record shops discovering classic Dylan records et al and it’s heartening to see them following that path. I’m never snobbish about it — I’d much prefer people discover stuff in their own way, rather than be compelled to follow fashion.”

Embracing the personal archive

Video game ownership is increasingly digital, meaning that a vinyl set for a given game can also serve as a physical piece of memorabilia (at least we at Laced are keen to push that line 🤑).

Caithness emphasises that a collection of physical media doesn’t have to mean shelves full of marketing tat: “It serves as a personal archive. If you’re really invested in a video game for example, having that hard copy of the soundtrack means you’re still going to be able to rediscover it in 30 years time.” As old-fashioned as vinyl seems, “it provides you with something for the future. You’re memorialising your time spent with that game.”

Joe Caithness, via his company Subsequent Mastering, offers mastering, restoration and audio transfer – www.subsequentmastering.com | Twitter: @subsequentUK | Facebook.com/SubsequentMastering You can also connect with @CaithnessJoe on Twitter, but beware of passionate left-leaning political banter!

Joe keeps a blog focusing on all elements of mastering audio for independent and DIY musicians – www.independentmastering.blogspot.co.uk

He mastered all of Laced Records’ 2017 output — check out our product round-up: Lacedrecords.co/blogs/news/laced-records-2017-release-round-up